Mangcho takes you deeper into workings of the human mind, the value of art, and the mimetic battleground of advertising.

1st Movement: Of Gloves and Totems

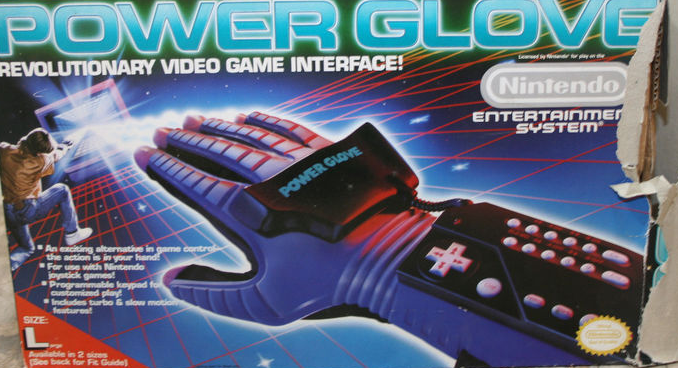

My colleague loaded up the Angry Video Game Nerd after a hard day of grading papers, and I decided to join him, surprised to know he was a fan. It was the Power Glove episode. The Nerd ranted about its many shortcomings as a video game peripheral–how it failed to deliver on everything promised, how it turned the basic controls of any game into a sloppy nightmare, and how much of an utter marketing bamboozle it turned out to be. Finally, he summarized his review with the nail in the coffin—the Power Glove was an overly expensive gimmick, meant to deceive rich kids into getting their parents to buy it for them. Suddenly, my colleague turns to me, a look of smug disdain on his face, and says, “There you go.”

I just shrugged and smirked, masking my embarrassment. When someone tries to take you down from the peg they imagine you’re at, when you really aren’t there, humility is often the better tactic. He didn’t know much about me, how I grew up, or what I had to deal with in my life. But I did let one detail slip. When we started watching the video, I told him I once owned a Power Glove. And since he’d grown up amidst some degree of poverty, the AVGN’s words produced an image of my life in his mind, based on the prejudices he held. I never came from wealth, but as a kid who owned a Nintendo product as indulgent and needless as the Glove, he thought he could read me like a book. With those three words, he expressed the embodiment of everything he hated about those with more, even if the disparity between us wasn’t as great as he’d thought. He had a belief in his head, regarding the poor, the rich, and his own childhood, that outweighed any nostalgic feelings for the Power Glove, or any cognitive dissonance around its deceptive marketing. His mind had been formed according to these beliefs, based on life experience, rendering him immune to the persuasive technique of the Mattel Corporation. Certain values of his had become antibodies to other, foreign values. Clearly, as a sheepish former Power Glove owner, I hadn’t been so lucky.

In the final paragraph of my last essay, I challenged you to draw a parallel between Sega’s confrontational marketing and the abandonment of stable values in western households, fueled by a Judaic understanding of the graven image and its mimetic power. What is this power? Assuming my colleague wasn’t lying, and hadn’t caved into the allure of the device (or wasn’t a self-hating rich kid, a common condition), he’d resisted the Power Glove’s mimetics because another set of memes got to him first, whether from his parents or on the playground. His desire to conform to these memes, these mimetic totems of understanding, rendered the Power Glove’s messaging feeble and unconvincing. If caving into the Glove meant toppling the totems he held dear, becoming either an apostate or hypocrite to them, he had no choice to resist, for the sake of his own dignity. This is the power of not merely mimetic, but totemic structures, which embed themselves into the psyche on a level so permanent as to be spiritual, so seemingly a priori as to confound sensation. To remove them would be to strip the flying buttresses off the Notre Dame, sending the whole basilica into a heap of rubble. It is through these totems that human minds, like the basilica, become a refuge for thought and emotion, for the mind and spirit, to hold firm against the storms of change, yet permitting light to shine through its stained glass windows, and allowing visitors to pass through its doors freely, without degrading its sanctity. The buttresses, the “totems” supporting the structure, are enough to keep it open without collapsing, and without losing its stability. The mimetic power of the totem, therefore, is not merely a reflection of human creative powers, realized upon the material world, through craft and labour. This is too superficial a sketch. No, the mimetic power is the way language is leveraged by the mimetic, radiating meaning through shape and form, colour and light, sequence and dialogue, sound and word, chapter and page.

But language must derive from somewhere, and must be receivable, in order to persist as a means of generating and receiving meaning. Taking this process as a given, the audience for these creative expressions is compelled to respond, even if only internally. They must pass judgement on what they have received. But this judgement is formed by, and grounded in, the totems supporting the subject’s mental structure, influencing the judgment they will arrive at. For over three centuries, Western thought has struggled to make the human subject the locus of meaning, as if meaning were some mystical, intangible property shot out by the subject upon the object, magically imbuing it with the meaning it, as an empty vessel, so desperately yearns for. There is, under this framework, no recognition of meaning as truly metaphysical, since this would place the source of meaning outside perception, which would overthrow the human subject’s sovereignty over his or her domain. However, this also means excluding the historical process from the meaning-making, since historical events cannot be directly experienced once locked in the past, presenting us with a bizarre neuroticism—the repression of objectivity as it concerns objects, to enable a solipsistic veneer of “empowerment” and “free choice”. The result is an aesthetic—modern, postmodern, relational—forever seeking to confound the inherent structures of the mind, disconnecting the subject from tradition.

I must confess, the ideas above are not particularly new. They have their roots in works such as Heidegger, Gadamer, Jean-Luc Marion, and Kant’s 3rd Critique, along with those I have not read. Despite my philosophical “re-serving” of a few treasured chestnuts, let us consider these forms of art among those whose totems are iconoclastic in nature. When the seduction of the graven image is considered too powerful to tolerate, or even harness for the purpose of worshipping God, the sight of others’ harnessing to this effect, and making this harnessing a public mission, presents a distasteful crisis for the iconoclast. It is no wonder, then, that the Jewish artworld has perennially rejected the notion of the incarnate in art, and strived to distort, disfigure, or under-represent the human form. Consider the early works of Rothko—gnarled, huddled forms, slumped and murky against indistinct, cloudy backgrounds; timid, emaciated denizens of the subway platform, peeking around pillars, morphing into the tile mosaic wall as if their humanity is seeping into the architecture. The discomfort with which the Jewish mind gleans the incarnate is palpable, making abstract expressionism, “found art”, and other “statements” of aesthetic infertility the only kosher havens. Even Walter Benjamin’s hyper-socialist view of photography, as “liberation” from direct experience, portrays a calcified aesthetic ethos, never able to distinguish the virtual from the real, the divine from the earthly, yet insisting on a pure divide between them.

The drive to push modernity to the forefront of Western thought, then, is not merely a consequence of capitalist benefits, eroding the traditional structures of agrarian life. Cities are nothing new to the West, nor is private investment. This is religious warfare, quietly waged upon canvases, celluloid, and strings of code. By the 1980s, advertising quickly became a mockery of the incarnate, of human forms radiating truth, of Gentile values and manners holding a place of esteem in civilized society. Children were especially targeted. You can have success, love, praise, freedom, so long as you never question the system. And what is the system, in the West of the 1980s? It is the Gentiles, terrified of repeating abuses that betrayed the Christian ethos they sought to uphold. It is the Jew, terrified of betraying a covenant by granting the alien a cubit more than God would permit. It is my colleague, reminding me I should be ashamed to have once owned a Power Glove, not because of what it is, but what it represents to him. His totems will not be challenged, and likewise, I will not let mine be. But perhaps the difference between us is not one of stable structures, but of how we see one another. Are his ideas the light and the people, streaming through the doors and windows of my mind’s basilica? Or are they the Moors at the edge of Avila’s walls, readying catapults against them? Is my colleague the enemy, or a visitor, interested in beholding what I hold dear?

In order to understand if my colleague is an enemy, I must be made sure. I must have facts which support this view. But most importantly, I must understand why. Judaic thought espouses similar goals as Nazism. The Master Race, the chosen people, sacrificing for their collective goals along tenuous ethnic lines—both ideologies carry the guilt of blood shed for these totems. Yet if I can become aware of why these people—my colleagues, our colleagues, and I theirs—would see me in this way, I can muster a defence, protect, serve, and even save.

Leave a Reply